Test Better

Developers take pride in speaking their mind and not shying away from touchy subjects. Yet there is one subject makes many developers uncomfortable.

Testing.

I’m not talking about drug testing, unit testing, or any form of automated testing. After all, while there are still some holdouts, at least these types of tests involve writing code. And we know how much developers love to write code (even though that’s not what we’re really paid to do).

No, I’m talking about the kind of testing where you get your hands dirty actually trying the application. Where you attempt to break the beautifully factored code you may have just written. At the end of this post, I’ll provide a tip using GitHub that’s helped me with this.

TDD isn’t enough

I’m a huge fan of Test Driven Development. I know, I know. TDD isn’t about testing as Uncle Bob sayeth from on high in his book, Agile Software Development, Principles, Patterns, and Practices,

The act of writing a unit test is more an act of design than of verification.

And I agree! TDD is primarily about the design of your code. But notice that Bob doesn’t omit the verification part. He simply provides more emphasis to the act of design.

In my mind it’s like wrapping a steak in bacon. The steak is the primary focus of the meal, but I sure as hell am not going to throw away the bacon! I know, half of you are hitting the reply button to suggest you prefer the bacon. Me too but allow me this analogy.

MMMM, gimme dat! Credit: Jason Lam CC-BY-SA-2.0

MMMM, gimme dat! Credit: Jason Lam CC-BY-SA-2.0

The problem I’ve found myself running into, despite my own advice to the contrary, is that I start to trust too much in my unit tests. Several times I’ve made changes to my code, crafted beautiful unit tests that provide 100% assurance that the code is correct, only to have customers run into bugs with the code. Apparently my 100% correct code has a margin of error. Perhaps Donald Knuth said it best,

Beware of bugs in the above code; I have only proved it correct, not tried it.

It’s surprisingly easy for this to happen. In one case, we had a UI gesture bound to a method that was very well tested. Our UI was bound to this method. All tests pass. Ship it!

Except when you actually execute the code, you find that there’s a certain situation where an exception might occur that causes the code to attempt to modify the UI on a thread other than the UI thread #sadtrombone. That’s tricky to catch in a unit test.

Getting Serious about Testing

When I joined the GitHub for Windows (GHfW) team, we were still in the spiking phase, constantly experimenting with the UI and code. We had very little in the way of proper unit tests. Which worked fine for two people working in the same code in the same room in San Francisco. But here I was, the new guy hundreds of miles away in Bellevue, WA without any of the context they had. So I started to institute more rigor in our unit and integration tests as the product transitioned to a focus on engineering.

But we still lacked rigor in regular non-automated testing. Then along comes my compatriot, Drew Miller. If you recall, he’s the one I cribbed my approach structuring unit tests from.

Drew really gets testing in all its forms. I first started working with him on the ASP.NET MVC team when he joined as a test lead. He switched disciplines from a developer to become a QA person because he wanted a venue to test this theories on testing and eventually show the world that we don’t need separate QA person. Yes, he became a tester so he could destroy the role, in order to save the practice.

In fact, he hates the term QA (which stands for Quality Assurance):

The only assurance you will ever have is that code has bugs. Testing is about confidence. It’s about generating confidence that the user’s experience is good enough. And it’s about feedback. It’s about providing feedback to the developer in lieu of a user in the room. Be a tester, don’t be QA.

On the GitHub for Windows team, we don’t have a tester. We’re all responsible for testing. With Drew on board, we’re also getting much better at it.

Testing Your Own Code and Cognitive Bias

There’s this common belief that developers shouldn’t test their own code. Or maybe they should test it, but you absolutely need independent testers to also test it as well. I used to fully subscribe to this idea. But Drew has convinced me it’s hogwash.

It’s strange to me how developers will claim they can absolutely architect systems, provide insights into business decisions, write code, and do all sorts of things better than the suits and other co-workers, but when it comes to testing. Oh no no no, I can’t do that!

I think it’s a myth we perpetuate because we don’t like it! Of course we can do it, we’re smart and can do most anything we put our minds to. We just don’t want to so we perpetuate this myth.

There is some truth that developers tend to be bad at testing their own code. For example, the goal of a developer is to write software as bug free as possible. The presence of a bug is a negative. And it’s human nature to try to avoid things that make us sad. It’s very easy to unconsciously ignore code paths we’re unsure of while doing our testing.

While a tester’s job is to find bugs. A bug is a good thing to these folks. Thus they’re well suited to testing software.

But this oversimplifies our real goals as developers and testers. To ship quality software. Our goals are not at odds. This is the mental switch we must make.

And We Can Do It!

After all, you’ve probably heard it said a million times, when you look back on code written several months ago, you tend to cringe. You might not even recognize it. Code in the brain has a short half-life. For me, it only takes a day before code starts to slip my mind. In many respects, when I approach code I wrote yesterday, it’s almost as if I’m someone else approaching the code.

And that’s great for testing it.

When I think I’m done with a feature or a block of code, I pull a mental trick. I mentally envision myself as a tester. My goal now is to find bugs in this code. After all, if I find them and fix them first, nobody else has to know. Whenever a customer finds a bug caused by me, I feel horrible. So I have every incentive to try and break this code.

And I’m not afraid to ask for help when I need it. Sometimes it’s as simple as brainstorming ideas on what to test.

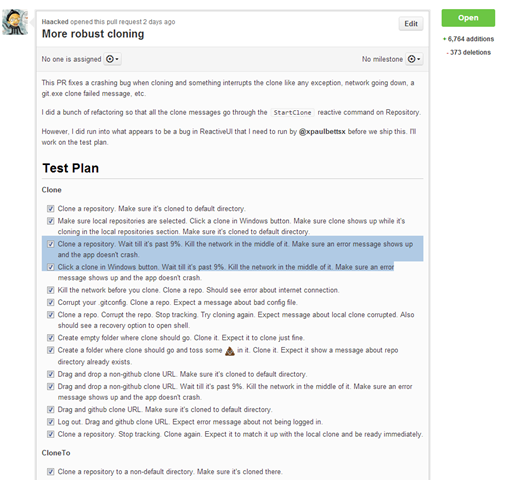

One trick that my team has started doing that I really love is when a feature is about done, we update the Pull Request (remember, a pull request is a conversation about some code and you don’t have to wait for the code to be ready to merge to create a PR) with a test plan using the new Task Lists feature via GitHub Flavored Markdown.

This puts me in a mindset to think about all the possible ways to break the code. Some of these items might get pulled from our master test plan or get added to it.

Here’s an example of a portion of a recent test plan for a major bug fix I worked on (click on it to see it larger).

The act of writing the test plan really helps me think hard about what could go wrong with the code. Then running through it just requires following the plan and checking off boxes. Sometimes as I’m testing, I’ll think of new cases and I’ll just edit the plan accordingly.

Also, the test plan can serve as an indicator to others that the PR is ready to be merged. When you see everything checked off, then it should be good to go! Or if you want to be more explicit about it, add a “sign-off” checkbox item. Whatever works best for you.

The Case for Testers

Please don’t use this post to justify firing your test team. The point I’m trying to make is that developers are capable of and should test their own (and each others) code. It should be a badge of pride that testers cannot find bugs in your code. But until you reach that point, you’re probably going to need your test team to stick around.

While my team does not have dedicated testers, we consider each of us to be testers. It’s a frame of mind we can put our minds into when we need to.

But we’re also not building software for the Space Shuttle so maybe we can get away with this.

I’m still of the mind that many teams can benefit from a dedicated tester. But the role this person has is different from the traditional rote mechanical testing you often find testers lumped into. This person would mentor developers in the testing part of building software. Help them get into that mindset. This person might also work to streamline whatever crap gets in the way so that developers can better test their code. For example, building automation that sets up test labs for various configuration in a moment’s notice. Or helping to verify incoming bug reports from customers.

Related Posts

Comments

24 responses