Abolish Performance Reviews

Who doesn’t love the smell of performance reviews in the morning? A smell welcomed by employees and managers alike with joy and delight. An efficient ritual that is fair and definitely motivates everyone to improve. A ritual that no one doubts is worth the investment of time and energy.

Yes, I’m kidding. No, I haven’t been hacked (I am and will always be haacked though).

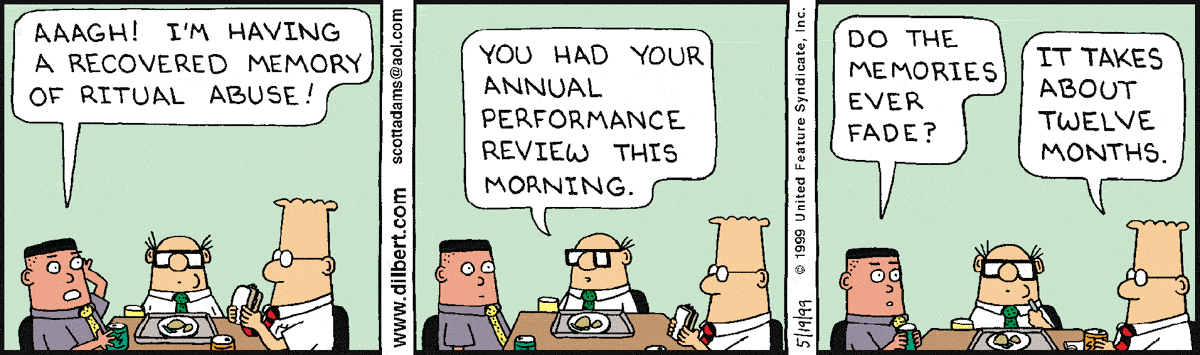

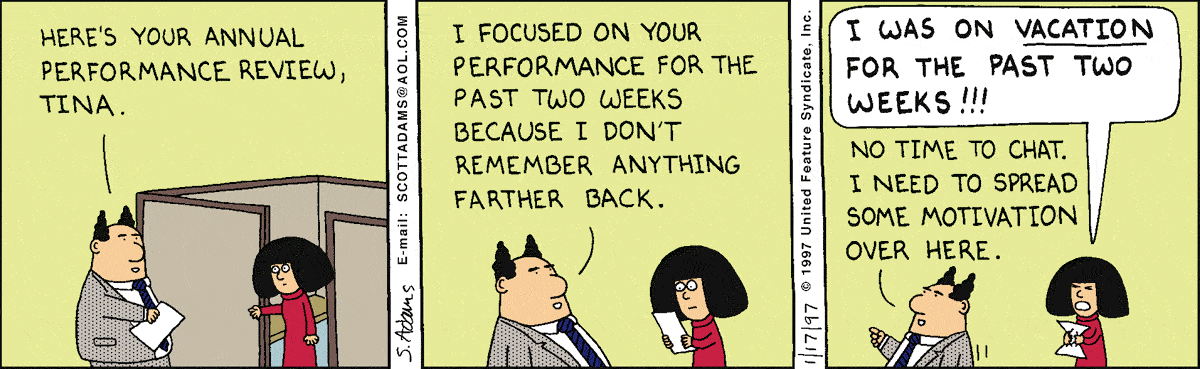

Dilbert can provide a better introduction to performance reviews:

Yes, it’s a crutch to quote Dilbert on a post about management, but forgive me. On this topic, Dilbert is so spot on. I’ll only do it twice, I promise. Now back to the point…

Companies should abolish the charade of annual (or semiannual) performance reviews.

They are expensive, biased, and they don’t work. Yet, companies persist in the Sisyphean attempt. They take it as a given that the dread and anxiety they create serves a noble purpose. It’s like believing that constant face slaps will lead to stronger cheek muscles.

It’s bullshit. Constant face slaps lead to a sore face.

As you can see, I’m pretty tepid about this issue. But a lot of researchers and experts are not. In this post I quote a lot of them, because I don’t expect anyone to take my word for it.

Let’s start with Dr. William Edwards Deming.

Deming’s Argument

The annual appraisal of performance, or the so-called merit system. Of all the forces of destruction that have beset American industry, this one has dealt the most powerful blow. It destroys people, our most important asset.

This quote is from The Merit System: The Annual Appraisal: Destroyer of People as included in The Essential Deming.

It’s hard to overstate how important Deming was to the field of business management. He changed the very idea of how businesses approach quality and organizational efficiency. His ideas on continuous improvement and total quality helped Japan recover from World War II and become an automotive powerhouse.

His focus went beyond process. He taught companies to create a culture of quality.

He goes on to describe why reviews fail people (emphasis mine).

The merit rating nourishes short-term performance, annihilates long-term planning, builds fear, demolishes teamwork, [and] nourishes rivalry and politics. It leaves people bitter, crushed, bruised, battered, desolate, despondent, dejected, feeling inferior, some even depressed, unfit for work for weeks after receipt of rating, unable to comprehend why they are inferior.

Tell me how you really feel, Deming. Deming goes on to note what reviews really reward.

The merit rating rewards people that conform to the system. It does not reward attempts to improve the system. Don’t rock the boat.

In case it’s not clear that Deming had a strong distaste for annual performance reviews, he lists them third in his Seven Deadly Diseases of Management list.

Reviews are Wildly Inaccurate

Not only do people dislike reviews, they are also unreliable. In the article, The Corporate Kabuki of performance reviews, the author notes,

They’re wildly inaccurate, for one: CEB’s research finds that two-thirds of employees who receive the highest scores in a typical performance management system are not actually the organization’s highest performers. Go figure.

The Push Against Performance Reviews adds more weight to this assertion.

Studies suggest that more than half of a given performance rating has to do with the traits of the person conducting the evaluation, not of the person being rated.

The article notes one source of inaccuracy,

Managers have incentives to inflate appraisals; even accurate feedback can feel biased and unfair, making people less motivated and hurting relationships between supervisors and subordinates; and organizations don’t do a good job of rewarding good evaluators and sanctioning bad ones. “As a result, annual appraisals end up as a source of anxiety and annoyance rather than a source of useful information,” Murphy wrote.

Women especially lose out

Performance reviews should be fair, but in practice they are fertile ground for bias.

The author of Valley Boys notes,

In a recent study of almost two hundred and fifty performance reviews, the tech entrepreneur Kieran Snyder found that three-quarters of the women were criticized for their personalities—with words like “abrasive”—while only two of the men were.

In How Gender Bias Corrupts Performance Reviews, and What to Do About It, Paola Cecchi-Dimeglio writes,

One of my findings, using content analysis of individual annual performance reviews, shows that women were 1.4 times more likely to receive critical subjective feedback (as opposed to either positive feedback or critical objective feedback).

Reviewers describe high-achieving men and women in different terms for the same behavior! In a study of 248 reviews conducted by Kieran Snyder.

Note that the gender of the manager did not impact these results. This is a clear example of implicit bias.

As if the odds weren’t stacked enough against women, it turns out that Men Get Credit for Voicing Ideas, but Not Problems. Women Don’t Get Credit for Either (emphasis mine).

Across both studies—using both field and experimental research designs and very different populations of respondents—we saw the same pattern of results: Men who spoke up with ideas were seen as having higher status and were more likely to emerge as leaders. Women did not receive any benefits in status or leader emergence from speaking up, regardless of whether they did so promotively or prohibitively. Neither men nor women who spoke up about problems suffered a loss of status or had a lower likelihood of emerging as a leader (though they weren’t helped by speaking up, either). Also of note, men and women both ascribed more status and leadership emergence to men who spoke up promotively, compared with women who did so.

They don’t even work

Do we forgive these flaws because reviews improve performance?

Not so, suggests the evidence. Performance appraisal’s fail at their primary goal, to improve performance.

Again, citing The Push Against Performance Reviews,

An earlier study, published in 1996, found that while job appraisals generally improved people’s performance, they had a negative impact on performance more than a third of the time, notably in cases where the assessments focused on individuals rather than on their performance at particular tasks.

More than a third of the time, they have a negative impact. But 2 out of 3 ain’t bad, right? Well, not so fast.

In Why Incentive Plans Cannot Work, we learn that any gains tend to be temporary.

Do rewards work? The answer depends on what we mean by “work.” Research suggests that, by and large, rewards succeed at securing one thing only: temporary compliance. When it comes to producing lasting change in attitudes and behavior, however, rewards, like punishment, are strikingly ineffective. Once the rewards run out, people revert to their old behaviors.

They do not create an enduring commitment to any value or action. Rather, incentives merely—and temporarily—change what we do.

Lazlo Bock, former head of people operations at Google backs this up in Work Rules!,

Intrinsic motivation is the key to growth, but conventional performance management systems destroy that motivation.

This aligns well with Dan Pink’s own research into what really motivates us.

Negative feedback has a negative effect

Rather than improve performance, reviews often have the opposite effect. Negative feedback demoralizes those with bad ratings.

The article Why Performance Reviews Don’t Improve Performance notes (emphasis mine),

Research by psychologists at Kansas State University, Eastern Kentucky University and Texas A&M University examined how people respond to negative feedback they receive in performance reviews. Conventional wisdom is that people who are really motivated to improve their performance would respond well to getting critical feedback in a performance review. The research demonstrated this wisdom is wrong.

In an article published in The Psychological Bulletin, psychologists A. Kluger and A. Denisi report completion of a meta-analysis of 607 studies of performance evaluations and concluded that at least 30 percent of the performance reviews ended up in decreased employee performance.

The Case Against Performance Reviews offers an explanation for this effect,

“We’d rather be ruined by praise than saved by criticism,” wrote Norman Vincent Peale, the author of the 1962 book The Power of Positive Thinking. It sounds like a glib aphorism, but that’s actually pretty close to the research consensus. Criticism stinks.

But what about workers who readily say they want to get better at their jobs—maybe they’d appreciate a critical nudge? Yeah, right. After administering negative feedback to both groups, the researchers found that the first group hated the feedback round, and the second group—employees with the strongest “learning-goal orientation”—was nearly as unhappy with the criticism.

The New Yorker - The Push Against Performance Reviews supports this assertion,

In 2013, psychologists at Kansas State University and other institutions studied how different kinds of people react to negative feedback. They invited more than two hundred employees of a university to rate how they felt about a recent performance evaluation, and asked questions meant to categorize the employees based on how they approach personal goals. The researchers figured that people who seek out learning opportunities would react better than those who avoid situations in which they might fail. This was true—but even the avid learners disliked performance reviews, they just disliked them less.

They focus on the wrong thing.

What does help improve performance? As mentioned before, Dan Pink’s research suggests intrinsic motivation. He notes three elements that increase intrinsic motivation: autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

Laszlo Bock notes that having clear goals also helps improve performance,

On the topic of goals, the academic research agrees with your intuition: Having goals improves performance. Intrinsic motivation is the key to growth, but conventional performance management systems destroy that motivation.

Performance reviews do not support any of these goals. They are also too focused on the individual and can harm teams.

In Incentive Pay Considered Harmful Joes Spolksy warns,

If you’re in this position, the only way to prevent teamicide is to simply give everyone on your team a gushing review. But if you do have any choice in the matter, I’d recommend that you run fleeing from any kind of performance review, incentive bonus, or stupid corporate employee-of-the-month program.

What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team describes Project Aristotle, research that Google conducted to find out what actually leads to high performing teams. The results were very interesting.

What interested the researchers most, however, was that teams that did well on one assignment usually did well on all the others. Conversely, teams that failed at one thing seemed to fail at everything. The researchers eventually concluded that what distinguished the ‘‘good’’ teams from the dysfunctional groups was how teammates treated one another. The right norms, in other words, could raise a group’s collective intelligence, whereas the wrong norms could hobble a team, even if, individually, all the members were exceptionally bright.

Performance reviews focus too much on individual ability. A collection of high achieving individuals does not ensure a high output team. Rather, psychological safety factors most in high output teams. The goal of any feedback process should be to create high performance teams. Instead, they produce individual vanity report cards.

They’re largely ignored

Employees ignore reviews for two main reasons:

- They put people on the defensive.

- Employers tie reviews to compensation.

The Corporate Kabuki of performance reviews highlights the first case,

Studies have shown over and over again, Jenkins says, that “people simply think they perform better than other people. Unless you rate someone in the highest category, the conversation shifts away from feedback and development to justification.”

“Ratings detract from the conversation,” says Stockdale. “If an employee is sitting there waiting for the number to drop, they’re not engaged in the conversation, at best. At worst, it can actually make them angry and disaffected for a period of up to a year.”

Most companies tie reviews to compensation and discuss both in the same conversation. This is a terrible mistake. Lazlo Bock explains,

At Google “Annual reviews happen in November, and pay discussions happen a month later.” “As Prasad Setty explains, “Traditional performance management systems make a big mistake. They combine two things that should be completely separate: performance evaluation and people development. Evaluation is necessary to distribute finite resources, like salary increases or bonus dollars. Development is just as necessary so people grow and improve.”

I have a bone to pick with that last part about “Evaluation is necessary to distribute finite resources,” but that’ll have to come in a follow-up blog post. The main point stands though.

Netflix also separates performance conversations from compensation conversations.

So why do continue to do them?

If performance reviews are so bad, why do they persist? Well for one thing, they’ve been around a long time.

The Case Against Performance Reviews notes,

one of the earliest examples of formal appraisal comes from China’s Wei Dynasty, around 230 AD, when an Imperial Rater invented a nine-grade system to evaluate members of the official family.

In his book, Out of the Crisis, Deming writes that he understands why companies are so bought into performance reviews…

The idea of a merit rating is alluring. The sound of the words captivates the imagination: pay for what you get; get what you pay for; motivate people to do their best, for their own good. The effect is exactly the opposite of what the words promise.

There’s also a lack of imagination for what to do instead.

As Laszlo Bock, former head of People Ops for Google notes in WORK RULES!,

The major problem with performance management systems today is that they have become substitutes for the vital act of actually managing people.

There’s also survivorship bias to contend with. As the Atlantic article notes,

Perhaps one specific group appreciates criticism: The workers least likely to be criticized.

It stands to reason that those who benefit most from reviews get the lion share of promotions. They tend to become in charge. It creates a natural incentive to perpetuate the system.

That last point may be the strongest reason they persist.

What should we do instead?

Give up and go live in a monastery in the mountains.

That might be a bit drastic. The answer to this question could be its own blog post. And someday I might try and tackle the question in more detail.

I don’t have all the answers, but I can I have a few ideas to share for now. The first is a suggestion by Seth Godin from Your soft skills inventory,

The annual review is a waste. It’s not particularly useful for employee or boss, it’s stressful and it doesn’t happen often enough to make much of an impact.

If you choose to, though, you can do your own review. Weekly or monthly, you can sit down with yourself (or, more powerfully, with a small circle of peers) and review how you’re shifting your posture to make more of an impact.

The Push Against Performance Reviews also advocates for informal check-ins,

Instead, Morris implemented a more informal “check-in” process that takes place throughout the year, with employees receiving feedback on what they’re working on at any given moment.

Netflix does this with informal 360-degree reviews,

When we stopped doing formal performance reviews, we instituted informal 360-degree reviews. We kept them fairly simple: People were asked to identify things that colleagues should stop, start, or continue. In the beginning we used an anonymous software system, but over time we shifted to signed feedback, and many teams held their 360s face-to-face.

The Case Against Performance Reviews suggest more diversity in the review process,

…involve a diverse group of people in the evaluation process to water down individual bias, as Jeffrey Pfeffer wrote in Bloomberg Businessweek. One-on-one evaluations can feel personal. Groups critiquing groups isn’t just more constructive; but also, it’s a realistic way to evaluate systems and workflow, which are often as important as individual merit in larger organizations.

My advice is to emphasize managers as trusted mentors and coaches, not as report card graders. Their focus should be to improve people and grow teams. They should provide continuous feedback with occasional informal check-ins on progress towards goals

At the very least, separate pay increases from performance evaluation because. Incentive pay does not work. Pay according to the market instead.

Experiment with approaches and follow up on results. It’s important to iterate on whatever approach you choose. As always, keep the end goal in mind and make sure the cost of whatever you implement is worth the benefit.

RESOURCES

- The Essential Deming

- Out of the Crisis - Deming

- Seven Deadly Diseases of Management - Deming

- The Corporate Kabuki of performance reviews - Washington Post

- The Push Against Performance Reviews - New Yorker

- The Case Against Performance Reviews - The Atlantic

- Valley Boys - New Yorker

- How Gender Bias Corrupts Performance Reviews, and What to Do About It - HBR

- The abrasiveness trap: High-achieving men and women are described differently in reviews - Fortune

- Men Get Credit for Voicing Ideas, but Not Problems. Women Don’t Get Credit for Either - HBR

- Why Incentive Plans Cannot Work - HBR

- What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team - NY Times

- Your soft skills inventory - Seth Godin

- How Netflix Reinvented HR - HBR

Comments

16 responses