Mile High Overview Of Subtext Skinning

In my previous post, I outlined some minor changes to the skinning model for Subtext. In this post, I will give a high level overview of how skinning works in Subtext.

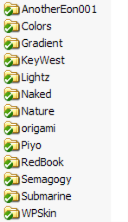

Subtext renders a Skin by combining a set of CSS stylesheets with a set of .ascx controls located in a specific skin folder. If you look in the Skins directory for example, you might see a set of folders like this.

Skin Template

A common misperception is that each folder represents a Skin. In fact, each folder represents something we call a Skin Template, and can be used to render multiple skins. One way to think of it is that each folder contains a family of skins.

Each folder contains a series of .ascx controls used to render each skin in that skin family as well as some CSS stylesheets and images used for individual skins or for the entire family.

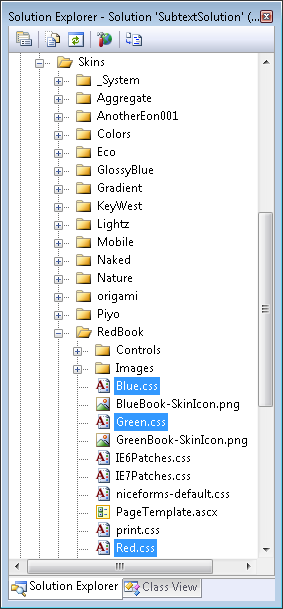

For example, the Redbook template folder contains three skins, Redbook, BlueBook, and GreenBook. In the screenshot below, we can see that there are three CSS stylesheets that specifically correspond to these three skins. How does Subtext know that these three stylsheets define three different skins while the other stylesheets in this folder do not?

The answer is that this is defined within the Skins.config file.

Skins.config

The Skins.config file is located in the Admin directory and contains

an XML definition for every skin. Here is a snippet of the file

containing the definition for the Redbook family of skins. This

snippet shows the definition of the BlueBook skin.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<SkinTemplates xmlns:xsd="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance">

<Skins>

<SkinTemplate Name="BlueBook"

TemplateFolder="RedBook"

StyleSheet="Blue.css">

<Scripts>

<Script Src="~/Admin/Resources/Scripts/niceForms.js" />

</Scripts>

<Styles>

<Style href="~/skins/_System/csharp.css" />

<Style href="~/skins/_System/commonstyle.css" />

<Style href="~/skins/_System/commonlayout.css" />

<Style href="niceforms-default.css" />

<Style href="print.css" media="print" />

</Styles>

</SkinTemplate>

</Skins>

</SkinTemplates>

There is a SkinTemplate node for each Skin within the system (I

know, not quite consistent now that I think of it. Should probably be

named Skin).

The Name attribute defines the name of this particular skin.

The TemplateFolder attribute specifies the physical skin template

folder in which the all the ascx controls and images are located in.

The StyleSheet attribute specifies which stylesheet defines the

primary CSS stylesheet for this skin.

For example, the GreenBook skin definition looks just like the

BlueBook skin definition except that the StyleSheet attribute

references Green.css instead of Blue.css.

Within the SkinTemplate node is a collection of Script nodes and a

collection of Style nodes. These specify any client scripts (such as

Javascript) and other CSS files that should be included when rendering

this skin. As you can see, the tilde (~) syntax works for specifying a

path to a file and a developer can specify a media and a conditional for

each CSS stylesheet.

Controls

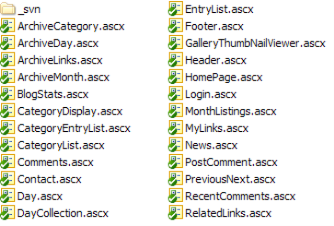

I keep mentioning that Subtext depends on a collection of .ascx user controls when it renders a family of skins. Let’s talk about them for a moment.

In the second screenshot above, you may have noticed a directory named Controls. This contains the bulk of the .ascx controls used to render a specific skin. There was also a control named PageTemplate.ascx in the parent directory.

Each skin in a family of skins is rendered by the same set of

UserControl instances. The only difference between two skins within

the same family is the CSS stylesheet used (which can account for quite

a difference as we learn from CSS Zen Garden).

The PageTemplate.ascx control defines the overall template for a skin, and then each of these user controls in the Controls directory is responsible for archiving a specific portion of the blog.

Select a different skin from another skin family, and Subtext will load

in a completely different set of UserControl files, that all follow

the same naming convention.

Drawbacks and Future Direction

This is one of the drawbacks to the current implementation. For

example, rather than using data binding syntax, each .ascx file is

required to define certain WebControl instances with specific IDs.

The underlying Subtext code then performs a FindControl searching for

these specific controls and sets their values in order to populate

them. This naming convention is often the most confusing part of

implementing a new skin for developers.

It used to be that if a WebControl was removed from an .ascx file

(perhaps you didn’t want to display a particular piece of information),

this would cause an exception as Subtext could not find that control.

We’ve tried to remedy that as much as possible.

In the future, we hope to implement a more flexible MasterPage based

approach in which the underlying code provides a rich data source and

each skin can bind to whichever data it wishes to display via data

binding syntax.

From a software perspective, this changes the dependency arrow in the opposite direction. Rather than the underlying code having to know exactly which controls a skin must provide, it will simply provide data and it is up to the individual skin to pick and choose which data it wishes to bind to.

Conclusion

We provided the Naked skin so that developers creating custom skins could play around with an absolutely bare-bone skin and see just how each of the controls participates in rendering a blog.

Comments

0 responses