Fun with infinite sums

I’m kind of a fan of numbers. You might even say I’m a bit of a numberPHILe. You groan, but it’s true. Numbers exhibit such interesting properties when you put them together.

Recently an “astounding result” from the Numberphile folks (see, I’m not the only one) on Youtube made its way around the internet. In this video, a couple of physicists “prove” that sum of all natural numbers results in -1/12 (or -0.08333… for you fraction haters). That is, if you take 1 + 2 + 3 + ... and keep adding the next number forever, the eventual sum is a negative fraction. Whatchoo talkin’ ‘bout, Willis?!

This result defies intuition. But as we’ll see, most results when dealing with infinities defy intuition.

In this particular video, they seem to play a bit fast and loose with the math. But there is a kernel of truth to what they demonstrate. I thought it’d be fun (for non-zero values of fun) to explore this idea a bit and throw some code at it to learn a thing or two. But first, I should warn you I am not a good mathematician. I have a tiny bit of undergraduate background in math, but some of the concepts I’ll explore are beyond my puny brain’s capacity. Feel free to send me a pull request with corrections!

But first, a joke

There’s another one later if you stick with it.

A mathematician will call an infinite series convergent if its terms go to zero. A physicist will call it convergent if the first term is finite.

This joke is funny to mathematicians because it pokes fun at the math ability of physicists. The joke is funny to me because it’s wrong about the mathematician. Any decent mathematician knows that the terms going to zero is necessary, but not sufficient for the series to converge. For example, the terms of the harmonic series go to zero, but its sum is positive infinity.

For those who need a refresher, it might help if I define what a sequence is and what a series is.

Definitions

A sequence is an ordered list of elements. The elements can be anything that can be ordered such as a sequence of your family members ordered by how much you love them. For our purposes, we’ll stick with numbers. A sequence can be finite or infinite. For infinite series, it’s prudent to have some mathematical formula that tells you how to determine each member of the sequence rather than attempt to write them out by hand. I don’t recommend this. Though it could come in handy if you ever need to disable an evil entity’s control over your computer by keeping the computer busy.

A partial sum is the sum of a finite portion of the sequence starting at the beginning. In looking at the harmonic series, this is like plugging in a specific value for n. So in the case of n = 1, the partial sum is 1. For n = 2, it’s 1.5. For n = 10 it’s a lot of addition.

A series is itself a sequence where each value represents the partial sum from 0 to n. A finite series will have a last term that represents the finite value that the series converges to. What often is counter intuitive is that an infinite series can also converge to a finite number as n goes to infinity. There’s no last term (it’s infinite), but we can use mathematical tools to determine the limit (the value the series approaches) for the series.

Infinite series with finite sums

Let’s look at an infinite series with a finite sum to prove that such a thing is possible. Zeno aside, intuition suggests that a series where each term approaches zero “fast enough” could result in a sum that is finite. The approach to zero just has to be “faster” than the growth via accumulation.

The following is known as the Basel Series where each member of the sequence is 1/n^2. In 1735, Leonhard Euler (pronounced “oiler”, not “yuler”), at the tender young age of 28, famously gave a proof for the exact value of this series as n goes to infinity. If you have a math symbol fetish, you can go read Euler’s proof here. There’s enough Greek there to write a tragedy.

Since I lack the brilliance of Euler, I’ll write some code to demonstrate this convergence because I have COMPUTERS! Eat it Euler!

The following method gets a partial sum of this series.

private static IEnumerable<double> GetEulerPartialSum(int n)

{

double sum = 0.0;

for (int i = 1; i <= n; i++)

{

sum += 1.0 / Math.Pow(i, 2);

yield return sum;

}

}

In a console program, we can iterate over this series.

static void Main(string[] args)

{

foreach (var partialSum in GetEulerPartialSum(1000000))

{

Console.SetCursorPosition(0, Console.CursorTop);

Console.Write(partialSum);

}

Console.ReadLine();

}

The reason for the SetCursorPosition call is to have each successive result overwrite the previous result. This way, you can watch the successive values change over time.

The first few decimal places converge in a near instant. It takes longer for the further out decimal places. As we get closer to 1 million iterations, we’re adding tiny increments to the sum. If I could run this program with an infinite number of iterations, every decimal place would eventually converge to a value. When I say “every” I mean all infinity of them.

Graph it

With C#, it’s not too hard to see a graph of this. Just add a reference to System.Windows.Forms.DataVisualization and add a Chart control to your application and add the following code:

First, we’ll slightly modify our previous method to return data points.

private static IEnumerable<DataPoint> GetEulerPartialSum(int n)

{

double sum = 0.0;

for (int i = 1; i <= n; i++)

{

sum += 1.0 / Math.Pow(i, 2);

yield return new DataPoint(i, (double)sum);

}

}

Next, we’ll add these data points to our chart.

chart.Series.Clear();

chart.Series.Add("euler");

chart.Series["euler"].ChartType = SeriesChartType.Line;

foreach (var point in GetEulerPartialSum(100))

{

chart.Series["euler"].Points.Add(point);

}

Here’s the result.

Look at how pretty that is.

Whoops, time for another math and theoretical physics joke

Ok, it’s been a while, let’s get back to the topic at hand.

What is the result of

1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ...?

The mathematician: I cannot respond if you do not say to me what it follows after the dots..

The physicist: it diverges!

Polchinski: = -1/12

Polchinksi was a string theorist.

So what’s the problem with the proof in the video? Well as we’ve seen, in order for a summation of a series to converge, the terms need to go to 0. But the first series they cover, Grandi’s Series, does not converge!

1 - 1 + 1 - 1 + 1 ...

Or more succinctly,

Here’s some code for it and the graph that results.

private static IEnumerable<DataPoint> GetGrandiPartialSum(int n)

{

double sum = 0.0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++)

{

sum += Math.Pow(-1, i);

yield return new DataPoint(i, sum);

}

}

As you can see, that looks very different. There’s no clear convergence to a single value. At every iteration, the partial sum is either 1 or 0!

So in the video, they mention that you could assign a value of 0.5 to this series. What they refer to is another way of assigning a sum to an infinite series. For example, a Cesàro summation is an approach where you take the average of the partial sums. This is slightly confusing so let me clarify. As we saw, the partial sum is either 0 or 1 at every iteration. If we sum up those partial sums at each iteration and divide it by the iteration, we get the average. That’s the Cesàro partial sum.

| n | Sum | Sum of Partial Sums | Average = (Sum of Sums / n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 1/2 = 0.5 |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 2/3 = 0.6666 |

| 4 | 0 | 2 | 2/4 = 0.5 |

| 5 | 1 | 3 | 3/5 = 0.6 |

| 6 | 0 | 3 | 3/6 = 0.5 |

As you can see, it appears to be converging to 0.5. So even though the Grandi series is divergent series and has an infinite sum, it is Cesàro summable and that sum is 0.5.

There’s some code and a graph again to visualize it.

private static IEnumerable<DataPoint> GetGrandiCesaroPartialSum(int n)

{

double sum = 0.0;

double sumOfSums = 0.0;

for (int i = 1; i <= n; i++)

{

sum += Math.Pow(-1, i);

sumOfSums += sum;

yield return new DataPoint(i, sumOfSums / i);

}

}

That’s kind of neat.

But here’s the thing, a Cesàro summation is not the same thing as a normal additive summation. You can think of its result as a different property of a series from the normal summation.

As an analogy, imagine that I show you two flat shapes and then provide a proof that the shapes cancel each other out by subtracting the perimeter of one from the area of the other. You’d probably call foul on that.

While not a perfect analogy, that’s pretty close to what the video shows because they treat the Cesàro sum of the series as if it were a convergent series while they perform various operations that only apply to convergent series to get to their result.

In particular, the way they shift the series and start adding them triggered my Spidey sense. That might work for a convergent series, but not for divergent.

Here’s a simple proof from Quora that shows how this leads to a contradiction. We’ll let S represent the sum of the natural numbers. Now, let’s subtract S from itself, but we’ll shift things over by one like they did in the video.

S = 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5...

-S = - 1 + 2 + 3 + 4...

----------------------------

0 = 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1...

Let’s subtract it from itself again shifted over by one.

0 = 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1...

-0 = - 1 + 1 + 1 + 1...

----------------------------

0 = 1

So here we’ve proven that 0 = 1. Mathematicians would call this a reductio ad absurdum which is latin for “that shit’s cray!” In other words, the premise leads to an absurd result.

So how do you get -1/12?

While I disagree with the way they get to their result, these guys are not stupid. Also, they literally point to an equation that shows the sum of natural numbers is -1/12 in a book.

IN A BOOK! Well that’s all you need to know, right? Well if you look closely at the text, you’ll see it mentions something about a “renormalization.”

Riemann zeta function and analytic continuations.

As I mentioned earlier, much like a shape has different properties such as area, height, and weight, a summation can have different properties. Or more accurately, there are different approaches to summing a series.

As I was working on this blog post, I learned that the Numberphile folks, who created the original video, produced a follow-on video that shows an alternate proof that takes advantage of the Riemann Zeta function and analytic continuations.

It’s worth a watch. They get into how this applies to string theory.

Analytic continuations are a technique to extend the domain of a function. Recall that a domain is the range of allowed inputs into a function. These are the inputs for which the function provides a valid output. Inputs outside of the domain might diverge to infinity, for example.

The Zeta function’s domain is for values greater than 1. As you approach 1, the values of the Zeta function diverge to infinity. But we (well not “we”, but mathematicians who have a clue what they’re doing) can cry “YOLO!” and apply analytic continuation to extend the Zeta function below 1 to see what happens.

When you plug in -1 to the zeta function, you get -1/12. By definition of the zeta function, that also happens to equal 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + .... So the zeta function is another way to assign a finite value to this divergent series.

To visualize this, look at this graph of the zeta function here, it diverges at x = 1. But if you continue to the left pass the divergence, you can see finite values again.

In the original formulation of this function, Euler allowed for the exponents to be real numbers greater than 1. That crazy cat Riemann took it further and generalized it to complex exponents. If you recall, a complex number is in the form of a real part added to an imaginary part. Rather than worry about the implications of “imaginary” numbers, think of complex numbers as coordinates where the real part is the x-axis and the imaginary part is the y-axis. In that regard, it becomes easy to imagine a series that diverges in one dimension but converges in another.

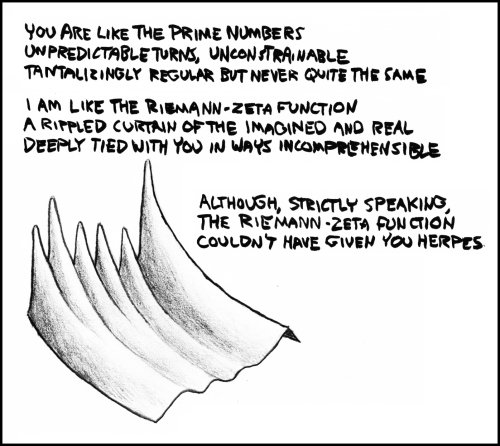

Graphing the Zeta function in this way produces some beautiful 3-D graphs as seen on Wolfram Alpha and immortalized by XKCD.

Incomprehensible indeed! When you deal with infinite series, it’s near impossible to have an intuitive handle on it. Our minds don’t deal with infinity very well, but our math does.

I hope you enjoyed this exploration. I can’t claim to know much about math, but I did find it fun to explore this idea with a bit of code and graphing. If you’re interested in the code I used, check out my “infinite sums” GitHub Repository.

If you’re looking for a practical use of this information, did you miss the part where I said it was math? LOL! But seriously, I thought of one practical use apart from describing 26 dimensional vibrating strings. The next time someone says you owe them money, just ask them if they’ll accept an amount equal to the sum of all natural numbers. If they accept, send them a bill for $-0.083.

Comments

25 responses