Applying Conway's Law

In some recent talks I make a reference to Conway’s Law named after Melvin Conway (not to be confused with British Mathematician John Horton Conway famous for Conway’s Game of Life nor to be confused with Conway Twitty) which states:

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.

Many interpret this as a cynical jibe at software management dysfunction. But this was not Melvin’s intent. At least it wasn’t his only intent. On his website, he quotes from Wikipedia, emphasis mine:

Conway’s law was not intended as a joke or a Zen koan, but as a valid sociological observation. It is a consequence of the fact that two software modules A and B cannot interface correctly with each other unless the designer and implementer of A communicates with the designer and implementer of B. Thus the interface structure of a software system necessarily will show a congruence with the social structure of the organization that produced it.

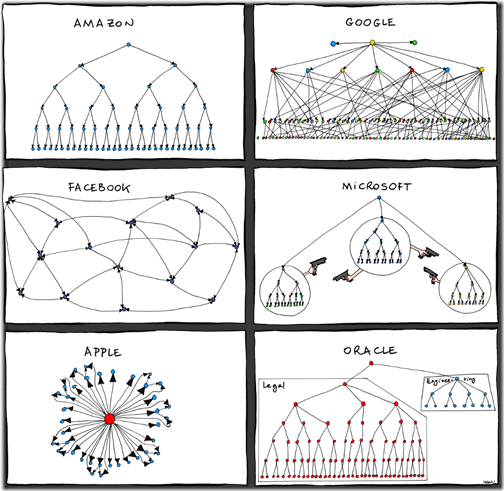

I savor Manu Cornet’s visual interpretation of Cornet’s law. I’m not sure how Manu put this together, but it’s not a stretch to suggest that the software architectures these companies produce might lead to these illustrations.

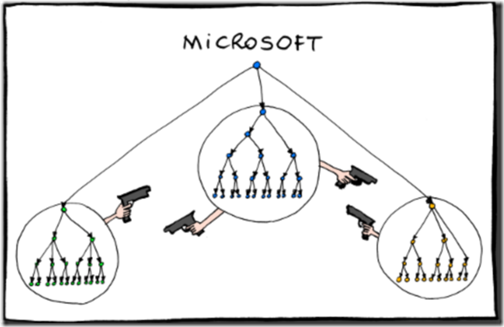

Having worked at Microsoft, the one that makes me laugh the most is the Microsoft box. Let’s zoom in on that one. Perhaps it’s an exaggerated depiction, but in my experience it’s not without some basis in truth.

The reason I mention Conway’s Law in my talks is to segue to the topic of how GitHub the company is structured. It illustrates why GitHub.com is structured the way it is.

So how is GitHub structured?

Well Zach Holman has written about it in the past where he talks about the distributed and asynchronous nature of GitHub. More recently, Ryan Tomayko gave a great talk (with associated blog post) entitled Your team should work like an open source project.

By far the most important part of the talk — the thing I hope people experiment with in their own organizations — is the idea of borrowing the natural constraints of open source software development when designing internal process and communication.

GitHub in many respects is structured like a set of open source projects. This is why GitHub.com is structured the way it is. It’s by necessity.

Like the typical open source project, we’re not all in the same room. We don’t work the same hours. Heck, many of us are not in the same time zones even. We don’t have top-down hierarchical management. This explains why GitHub.com doesn’t focus on the centralized tools or reports managers often want as a means of controlling workers. It’s a product that is focused more on the needs of the developers than on the needs of executives. It’s a product that allows GitHub itself to continue being productive.

Apply Conway’s Law

So if Conway’s Law is true, how can you make it work to your advantage? Well by restating it as Jesse Toth does according to this tweet by Sara Mei:

Conway’s Law restated by @jesse_toth: we should model our teams and our communication structures after the architecture we want. #scotruby

Conway’s Law in its initial form is passive. It’s an observation of how software structures tend to follow social structures. So it only makes sense to move from observer to active participant and change the organizational structures to match the architecture you want to produce.

Do you see the effects of Conway’s Law in the software you produce?

Comments

7 responses