Named Formats Redux

UPDATE: Be sure to read Peli’s post in which he explores all of these implementations using PEX. Apparently I have a lot more unit tests to write in order to define the expected behavior of the code.

I recently wrote a post in which I examined some existing implementations of named format methods and then described the fun I had writing a routine for implementing named formats.

In response to that post, I received two new implementations of the method that are worth calling out.

The first was sent to me by Atif Aziz, who I’ve corresponded with via email regarding Jayrock. He noticed that the slowest format method by James had one obvious performance flaw and fixed it up. He then sent me another version that passed all my unit tests. Here it is in full, and it’s much faster than before.

public static class JamesFormatter

{

public static string JamesFormat(this string format, object source)

{

return FormatWith(format, null, source);

}

public static string FormatWith(this string format

, IFormatProvider provider, object source)

{

if (format == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException("format");

List<object> values = new List<object>();

string rewrittenFormat = Regex.Replace(format,

@"(?<start>\{)+(?<property>[\w\.\[\]]+)(?<format>:[^}]+)?(?<end>\})+",

delegate(Match m)

{

Group startGroup = m.Groups["start"];

Group propertyGroup = m.Groups["property"];

Group formatGroup = m.Groups["format"];

Group endGroup = m.Groups["end"];

values.Add((propertyGroup.Value == "0")

? source

: Eval(source, propertyGroup.Value));

int openings = startGroup.Captures.Count;

int closings = endGroup.Captures.Count;

return openings > closings || openings % 2 == 0

? m.Value

: new string('{', openings) + (values.Count - 1)

+ formatGroup.Value

+ new string('}', closings);

},

RegexOptions.Compiled

| RegexOptions.CultureInvariant

| RegexOptions.IgnoreCase);

return string.Format(provider, rewrittenFormat, values.ToArray());

}

private static object Eval(object source, string expression)

{

try

{

return DataBinder.Eval(source, expression);

}

catch (HttpException e)

{

throw new FormatException(null, e);

}

}

}

The other version I got was from another Microsoftie named Henri Wiechers (no blog) who pointed out that a state machine of the sort that a parser or scanner would use, is well suited for this task. It also makes the code easier to understand if you’re accustomed to state machines.

public static class HenriFormatter

{

private static string OutExpression(object source, string expression)

{

string format = "";

int colonIndex = expression.IndexOf(':');

if (colonIndex > 0)

{

format = expression.Substring(colonIndex + 1);

expression = expression.Substring(0, colonIndex);

}

try

{

if (String.IsNullOrEmpty(format))

{

return (DataBinder.Eval(source, expression) ?? "").ToString();

}

return DataBinder.Eval(source, expression, "{0:" + format + "}")

?? "";

}

catch (HttpException)

{

throw new FormatException();

}

}

public static string HenriFormat(this string format, object source)

{

if (format == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException("format");

}

StringBuilder result = new StringBuilder(format.Length * 2);

using (var reader = new StringReader(format))

{

StringBuilder expression = new StringBuilder();

int @char = -1;

State state = State.OutsideExpression;

do

{

switch (state)

{

case State.OutsideExpression:

@char = reader.Read();

switch (@char)

{

case -1:

state = State.End;

break;

case '{':

state = State.OnOpenBracket;

break;

case '}':

state = State.OnCloseBracket;

break;

default:

result.Append((char)@char);

break;

}

break;

case State.OnOpenBracket:

@char = reader.Read();

switch (@char)

{

case -1:

throw new FormatException();

case '{':

result.Append('{');

state = State.OutsideExpression;

break;

default:

expression.Append((char)@char);

state = State.InsideExpression;

break;

}

break;

case State.InsideExpression:

@char = reader.Read();

switch (@char)

{

case -1:

throw new FormatException();

case '}':

result.Append(OutExpression(source, expression.ToString()));

expression.Length = 0;

state = State.OutsideExpression;

break;

default:

expression.Append((char)@char);

break;

}

break;

case State.OnCloseBracket:

@char = reader.Read();

switch (@char)

{

case '}':

result.Append('}');

state = State.OutsideExpression;

break;

default:

throw new FormatException();

}

break;

default:

throw new InvalidOperationException("Invalid state.");

}

} while (state != State.End);

}

return result.ToString();

}

private enum State

{

OutsideExpression,

OnOpenBracket,

InsideExpression,

OnCloseBracket,

End

}

}

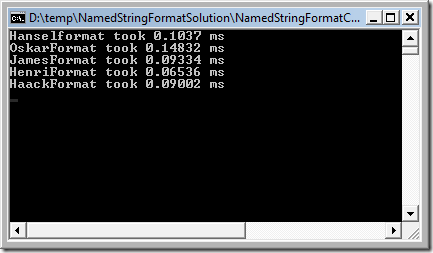

As before, I wanted to emphasize that this was not a performance contest. I was interested in correctness with reasonable performance.

Now that the JamesFormatter is up to speed, I was able to crank up the

number of iterations to 50,000 without testing my patience and tried it

again. I also made the format string slightly longer. Here are the new

results.

As

you can see, they are all very close, though Henri’s method is the

fastest.

As

you can see, they are all very close, though Henri’s method is the

fastest.

I went ahead and updated the solution I had uploaded last time so you can try it yourself by downloading it now.

Comments

23 responses