Trust and NuGet

How can you trust anything you install from NuGet? It’s a simple question, but the answer is complicated. Trust is not some binary value. There are degrees of trust. I trust my friends to warn me before they contact the authorities and maybe suggest a lawyer, but I trust my wife to help me dispose of the body and uphold the conspiracy of silence (Honey, it was in the fine print of our wedding vows in case you’re wondering).

The following are some ideas I’ve been bouncing around with the NuGet team about trust and security since even before I left NuGet. Hopefully they spark some interesting discussions about how to make NuGet a safer place to install packages.

Establish Identity and Authorship

The question “do I trust this package” is not the best question to ask. The more pertinent question is “do I trust the author of this package?”

NuGet doesn’t change how you go about answering this question yet. Whether you found a zip file on some random website or install it via NuGet, you still have to answer the following questions (perhaps unconsciously):

- Who is the author?

- Is the author trustworthy?

- Do I trust that the this software really was written by the author?

- Is the author’s means of distributing software tamper resistant and verifiable?

In some cases, the non-NuGet software is signed with a certificate. That helps answer questions 1, 2, and 3. But chances are, you don’t restrict yourself to only using certificate signed libraries. I looked through my own installed Visual Studio Extensions and several were not certificate signed.

NuGet doesn’t yet support package signing, but even if it did, it wouldn’t solve this problem sufficiently. If you want to know more why I think that, read the addendum about package signing at the end of this post.

What most people do in such situations is try to find alternate means to establish identity and authorship:

- I look for other sites that link to this package and mention the author.

- I look for sites that I already know to be in control of the author (such as a blog or Twitter account) and look for links to the package.

- I look for blog posts and tweets from other people I trust mentioning the package and author.

I think NuGet really needs to focus on making this better.

A Better Approach

There isn’t a single solution that will solve the problem. But I do believe a multipronged approach will make it much easier for people to establish the identity and authorship of a package and make an educated decision on whether or not to install any given package.

Piggy back on other verification systems

This first idea is a no-brainer to me. I’m a lazy bastard. If someone else has done the hard work, I’d like to build on what they’ve done.

This is where social media can come into play and have a useful purpose beyond telling the world what you ate for lunch.

For example, suppose you want to install RouteMagic and you see that the package owner is some user named haacked on NuGet. Who is this joker?

Hey! Maybe you happen to know haacked on GitHub! Is that the same guy as this one? You also know a haacked on Twitter and you trust that guy. Can we tie all these identities together?

Well it’d be easy through Oauth. The NuGet gallery could allow me to verify that I am the same person as haacked on GitHub and Twitter by doing an Oauth exchange with those sites. Only the real haacked on Twitter could authenticate as haacked on Twitter.

The more identities I attach to my NuGet account, the more you can trust that identity. It’s unlikely someone will hack both my GitHub and Twitter accounts.

The NuGet Gallery would need to expose these verifications in the UI anywhere I see a package owner, perhaps with little icons.

With Twitter, you could go even further. Twitter has the concept of verified identities. If we trust their process of verification, we could piggyback on that and show a verified icon next to Twitter verified users, adding more weight to your claimed identity.

This would be so easy and cheap to implement and provide a world of benefit for establishing identity.

Build our own verification system

Eventually, I think NuGet might want to consider having its own verification system and NuGet Verified Accounts™. This is much costlier than my previous suggestion to do it right and not simply favor corporations over the little guy.

Honestly, if we implemented the first idea well, I’m not sure this would ever have to happen anytime soon.

Vouching

This idea is inspired by the concept of a Web of Trust with PGP which provides a decentralized approach to establishing the identity of the owner of a public key.

While the previous ideas help establish identity, we still don’t know if we can trust these people. Chances are, if someone has a well established identity they won’t want to smudge their reputation with malware. But what about folks without well established reputations?

We could implement a system of vouching. For example, suppose you trust me and I vouch for ten people. And they in turn vouch for ten people each. That’s a network of 111 potentially trustworthy people. Of course, each degree you move out, the level of trust declines. You probably trust me more than the people I trust. And those people more than the people they trust. And so on.

How do we use this information in NuGet?

It could be as simple as factoring it into sort order. For example, one factor in establishing trust in a package today is looking at the download count of a package. Chances are that a malware library is not going to get ten thousand downloads.

We could also incorporate the level of trust of the package owner into that sort order. For example, show me packages for sending emails in order of trust and download count.

Other attack vectors

So far, I’ve focused on establishing trust in the author of a package. But a package manager system has other attack vectors.

For example, the place where packages are stored could be hacked or the service itself could be hacked.

If Azure Blob storage was hacked, an attacker could swap out packages of trusted authors with untrusted materials. This is a real concern. NuGet.org luckily stores the hash of each package and presents it in the feed. The NuGet client verifies the contents before installing it on the users machine.

However, suppose NuGet.org database was hacked. There is still a level of protection because any hash tampering would be caught by the clients.

An attacker would have to compromise both the Azure Blob Storage and the NuGet.org database.

Or worse, if the attacker compromises the machine that hosts NuGet, then it’s game over as they could corrupt the hashes and run code to pull packages from another location.

Mitigations of this nightmare scenario include having different credentials for Blobs and the database and constant security reviews of the NuGet code base.

Another thing we should consider is storing package hashes in packages.config so that Package Restore could at least verify packages during a restore in this nightmare scenario. But this wouldn’t solve the issue with installing new packages.

PowerShell Scripts

NuGet makes use of PowerShell scripts to perform useful tasks not covered by a typical package.

A lot of folks get worried about this as an attack vector and want a way to disable these scripts. There are definitely bad things that could happen and I’m not opposed to having an option to disable them, but this only gives a false sense of security. It’s security theater.

Why’s that you say? Well a package with only assemblies can still bite you through the use of Module Initializers.

Modules may contain special methods called module initializers to initialize the module itself.

All modules may have a module initializer. This method shall be static, a member of the module, take no parameters, return no value, be marked with rtspecialname and specialname, and be named .cctor.

There are no limitations on what code is permitted in a module initializer. Module initializers are permitted to run and call both managed and unmanaged code.

…

The module’s initializer method is executed at, or sometime before, first access to any types, methods, or data defined in the module

If you’re installing a package, you’re about to run some code with or without PowerShell scripts. The proper mitigation is to stop running your development environment as an administrator and make sure you trust the package author before you install the package.

At least with NuGet, when you install a package it doesn’t require elevation. If you install an MSI, you’d typically have to elevate privileges.

Addendum: Package Signing is not the answer

Every time I talk about NuGet security, someone gets irate and demands that we implement signing immediately as if it were some magic panacea. I’m definitely not against implementing package signing, but let’s be clear. It is a woefully inadequate solution in and of itself and there’s a lot better things we should do first as I’ve already outlined in this post.

The Cost and Ubiquity Problem

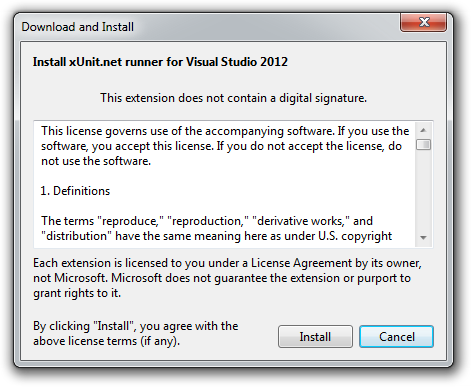

Very few people will sign their packages. Ruby Gems supports package signing and I’ve been told the number that take advantage of it is nearly zero. Visual Studio Extensions also supports package signing. Quick, go look at your list of installed extensions. Were any unsigned?

The problem is this, if you require certificate signing, you’ve just created too much friction to create a package and the package manager ecosystem will dry up and die. Requiring signing is just not an option.

The reason is that obtaining and properly signing software with a certificate is a costly proposition by its very nature. A certificate implies that some authority has verified your identity. For that verification to have value, it must be somewhat reliable and thorough. It’s not going to be immediate and easy or bad agents could easily do it.

Package signing is only a good solution if you can guarantee near ubiquity. Otherwise you still need alternative solutions.

The User Interface Problem

Once you allow package signing, you then have the user interface problem. Visual Studio Extensions is an interesting example of this conundrum. You only see that a package is digitally signed after you’ve downloaded and decided to install it. At that point, you tend to be committed already.

Also notice that the message that this package isn’t signed is barely noticeable.

Ok, so it’s not signed. What can I do about it other that probably Install it anyways because I really want this software. The fact that a package was signed didn’t change my behavior in any way.

Visual Studio could put more dire looking warnings, but it would alienate the community of extension authors by doing so. It could require signing, but that would put onerous restrictions on creating packages and would cause the community of signed packages to wither away, leaving only packages sponsored by corporations.

The point here is that even with signed packages, there’s not much it would do for NuGet. Perhaps we could support a mode where it gave a more dire warning or even disallowed unsigned packages, but that’d just be annoying and most people would never use that mode because the selection of packages would be too small.

The only benefit in this case of signing is that if a package did screw something up, you could probably chase down the author if they signed it. But that’s only a benefit if you never install unsigned packages. Since most people won’t sign them, this isn’t really a viable way to live.

Conclusion

Just to be clear. I’m actually in favor of supporting package signing eventually. But I do not support requiring package signing to make it into the NuGet gallery. And I think there are much better approaches we can take first to mitigate the risk of using NuGet before we get to that point.

I worry that implementing signing just gives a false sense of security and we need to consider all the various ways that people can establish trust in packages and package authors.

If you’re interested in more thoughts on this, check out my follow-up post, Why NuGet Package Signing Is Not (Yet) For Me.

Comments

29 responses