Fun With Named Formats, String Parsing, and Edge Cases

TRIPLE UPDATE! C# now has string interpolation which pretty much makes this post unnecessary and only interesting as a fun coding exercise.

DOUBLE UPDATE! Be sure to read Peli’s post in which he explores all of these implementations using PEX. Apparently I have a lot more unit tests to write in order to define the expected behavior of the code.

UPDATE: By the way, after you read this post, check out the post in which I revisit this topic and add two more implementations to check out.

Recently I found myself in a situation where I wanted to format a string using a named format string, rather than a positional one. Ignore for the moment the issue on whether this is a good idea or not, just trust me that I’ll be responsible with it.

The existing String.Format method, for example, formats values

according to position.

string s = string.Format("{0} first, {1} second", 3.14, DateTime.Now);

But what I wanted was to be able to use the name of properties/fields, rather than position like so:

var someObj = new {pi = 3.14, date = DateTime.Now};

string s = NamedFormat("{pi} first, {date} second", someObj);

Looking around the internet, I quickly found three implementations mentioned in this StackOverflow question.

- A Smarter (or Pure Evil) ToString with Extension Methods by Scott Hanselman.

- C#: String.Inject() – Format strings by key tokens from Oskar.

- FormatWith 2.0 – String Formatting with named variables by James Newton-King.

All three implementations are fairly similar in that they all use

regular expressions for the parsing. Hanselman’s approach is to write an

extension method of object (note that this won’t work in VB.NET until

they allow extending object). James and Oskar wrote extension methods

of the string class. James takes it a bit further by using

DataBinder.Eval on each token, which allows you to have formats such

as {foo.bar.baz} where baz is a property of bar which is a property

of foo. This is something else I wanted, which the others do not

provide.

He also makes good use of the MatchEvaluator delegate argument to the

Regex.Replace method, perhaps one of the most underused yet powerful

features of the Regex class. This ends up making the code for his

method very succinct.

Handling Brace Escaping

I hade a chat about this sort of string parsing with Eilon recently and he mentioned that many developers tend to ignore or get escaping wrong. So I thought I would see how these methods handle a simple test of escaping the braces.

String.Format with the following:

Console.WriteLine(String.Format("{{{0}}}", 123));

produces the output (sans quotes) of “{123}”

So I would expect with each of these methods, that:

Console.WriteLine(NamedFormat("{{{foo}}}", new {foo = 123}));

Would produce the exact same output, “{123}”. However, only James’s method passed this test. But when I expanded the test to the following format, “{{{{{foo}}}}}”, all three failed. That should have produced “{{123}}”.

Certainly this is not such a big deal as this really is an edge case, but you never know when an edge case might bite you as Zune owners learned recently. More importantly, it poses an interesting problem - how do you handle this correctly? I thought it would be fun to try.

This is possible to handle correctly using regular expressions, but it’s challenging. Not only are you dealing with balanced matching, but the matching depends on whether the number of consecutive braces are odd or even.

For example, the following “{0}}” is not valid because the right end brace is escaped. However, “{0}}}” is valid. The expression is closed with the leftmost end brace, which is followed by an even number of consecutive braces, which means they are all escaped sequences.

Performance

As I mentioned earlier, only James’s method handles evaluation of

sub-properties/fields via the use of the DataBinder.Eval method.

Critics of his blog post point out that this is a performance killer.

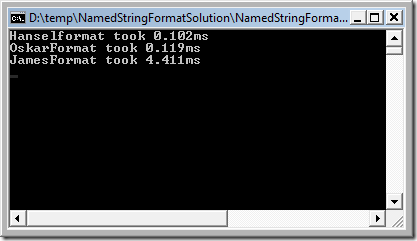

Personally, until I’ve measured it in the scenarios in which I plan to use it, I doubt that the performance will really be an issue compared to everything else going on. But I thought I would check it out anyways, writing a simple console app which runs each method over 1000 iterations, and then divides by 1000 to get the number of milliseconds each method takes. Here’s the result:

Notice that James’s method is 43 times slower than Hanselman’s. Even so, it only takes 4.4 milliseconds. So if you don’t use it in a tight loop with a lot of iterations, it’s not horrible, but it could be better.

My Implementation

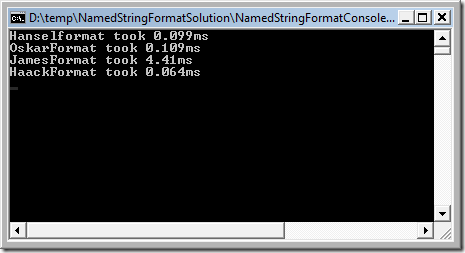

At this point, I thought it would be fun to write my own implementation using manual string parsing rather than regular expressions. I’m not sure my regex-fu is capable of handling the challenges I mentioned before. After implementing my own version, I ran the performance test and saw the following result.

Nice! by removing the overhead of using a regular expression in this

particular case, my implementation is faster than the other

implementations, despite my use of DataBinder.Eval. Hopefully my

implementation is correct, because fast and wrong is even worse than

slow and right.

One drawback to not using regular expressions is that the code for my implementation is a bit long. I include the entire source here. I’ve also zipped up the code for this solution which includes unit tests as well as the implementations of the other methods I tested, so you can see which tests they pass and which they don’t pass.

The core of the code is in two parts. One is a private method which

parses and splits the string into an enumeration of segments represented

by the ITextExpression interface. The method you call joins these

segments together, evaluating any expressions against a supplied object,

and returning the resulting string.

I think we could optimize the code even more by joining these operations into a single method, but I really liked the separation between the parsing and joining logic as it helped me wrap my head around it. Initially, I hoped that I could cache the parsed representation of the format string since strings are immutable thus I could re-use it. But it didn’t end up giving me any real performance gain when I measured it.

public static class HaackFormatter

{

public static string HaackFormat(this string format, object source)

{

if (format == null) {

throw new ArgumentNullException("format");

}

var formattedStrings = (from expression in SplitFormat(format)

select expression.Eval(source)).ToArray();

return String.Join("", formattedStrings);

}

private static IEnumerable<ITextExpression> SplitFormat(string format)

{

int exprEndIndex = -1;

int expStartIndex;

do

{

expStartIndex = format.IndexOfExpressionStart(exprEndIndex + 1);

if (expStartIndex < 0)

{

//everything after last end brace index.

if (exprEndIndex + 1 < format.Length)

{

yield return new LiteralFormat(

format.Substring(exprEndIndex + 1));

}

break;

}

if (expStartIndex - exprEndIndex - 1 > 0)

{

//everything up to next start brace index

yield return new LiteralFormat(format.Substring(exprEndIndex + 1

, expStartIndex - exprEndIndex - 1));

}

int endBraceIndex = format.IndexOfExpressionEnd(expStartIndex + 1);

if (endBraceIndex < 0)

{

//rest of string, no end brace (could be invalid expression)

yield return new FormatExpression(format.Substring(expStartIndex));

}

else

{

exprEndIndex = endBraceIndex;

//everything from start to end brace.

yield return new FormatExpression(format.Substring(expStartIndex

, endBraceIndex - expStartIndex + 1));

}

} while (expStartIndex > -1);

}

static int IndexOfExpressionStart(this string format, int startIndex) {

int index = format.IndexOf('{', startIndex);

if (index == -1) {

return index;

}

//peek ahead.

if (index + 1 < format.Length) {

char nextChar = format[index + 1];

if (nextChar == '{') {

return IndexOfExpressionStart(format, index + 2);

}

}

return index;

}

static int IndexOfExpressionEnd(this string format, int startIndex)

{

int endBraceIndex = format.IndexOf('}', startIndex);

if (endBraceIndex == -1) {

return endBraceIndex;

}

//start peeking ahead until there are no more braces...

// }}}}

int braceCount = 0;

for (int i = endBraceIndex + 1; i < format.Length; i++) {

if (format[i] == '}') {

braceCount++;

}

else {

break;

}

}

if (braceCount % 2 == 1) {

return IndexOfExpressionEnd(format, endBraceIndex + braceCount + 1);

}

return endBraceIndex;

}

}

And the code for the supporting classes

public class FormatExpression : ITextExpression

{

bool _invalidExpression = false;

public FormatExpression(string expression) {

if (!expression.StartsWith("{") || !expression.EndsWith("}")) {

_invalidExpression = true;

Expression = expression;

return;

}

string expressionWithoutBraces = expression.Substring(1

, expression.Length - 2);

int colonIndex = expressionWithoutBraces.IndexOf(':');

if (colonIndex < 0) {

Expression = expressionWithoutBraces;

}

else {

Expression = expressionWithoutBraces.Substring(0, colonIndex);

Format = expressionWithoutBraces.Substring(colonIndex + 1);

}

}

public string Expression {

get;

private set;

}

public string Format

{

get;

private set;

}

public string Eval(object o) {

if (_invalidExpression) {

throw new FormatException("Invalid expression");

}

try

{

if (String.IsNullOrEmpty(Format))

{

return (DataBinder.Eval(o, Expression) ?? string.Empty).ToString();

}

return (DataBinder.Eval(o, Expression, "{0:" + Format + "}") ??

string.Empty).ToString();

}

catch (ArgumentException) {

throw new FormatException();

}

catch (HttpException) {

throw new FormatException();

}

}

}

public class LiteralFormat : ITextExpression

{

public LiteralFormat(string literalText) {

LiteralText = literalText;

}

public string LiteralText {

get;

private set;

}

public string Eval(object o) {

string literalText = LiteralText

.Replace("{{", "{")

.Replace("}}", "}");

return literalText;

}

}

I mainly did this for fun, though I plan to use this method in Subtext for email fomatting.

Let me know if you find any situations or edge cases in which my version fails. I’ll probably be adding more test cases as I integrate this into Subtext. As far as I can tell, it handles normal formatting and brace escaping correctly.

Comments

48 responses