Voting is a Sham! Mathematically Speaking.

The recent elections remind me of interesting paradoxes when you study the mathematics of voting. I first learned of this class of paradoxes as an undergraduate at Occidental College in Los Angeles (well technically Eagle Rock, emphasis always on the Rock!). As a student, I spent a couple of summers as an instructor for OPTIMO, a science and math enrichment program for kids about to enter high school. You know, that age when young men and women’s minds are keenly focused on mathematics and science. What could go wrong?!

For several weeks, these young kids would stay in dorm rooms during the week and attend classes on a variety of topics. Many of these classes were taught by full professors, while others were taught by us student instructors. Every Friday they’d go home for the weekend and leave us instructors with a little time for rest and relaxation that we mostly used to gossip about the kids. I am convinced that programs like this are the inspiration for reality television shows such as The Real World and The Jersey Shore given the amount of drama these teenage kids could pack in a few short weeks.

But as per the usual, I digress.

So how do you keep the attention of a group of hormonally charged teenagers? I still don’t know, but I gave it the best effort. I was always on the lookout for little math nuggets that defied conventional wisdom. One such problem I ran into was the voting paradox.

Voting is a method that a group of people use to pick the “best choice” out of a set of candidates. It’s pretty obvious, right? When you have two choices, the method of voting is pretty obvious. Majority wins! But when you have more than two choices, things become interesting.

Suppose

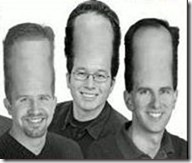

you have a contest for the best (not biggest) forehead between three

candidates. I’ll use my former forehead endowed co-authors for this

example.

Suppose

you have a contest for the best (not biggest) forehead between three

candidates. I’ll use my former forehead endowed co-authors for this

example.

You’ll notice I left out last year’s winner, Rob Conery, to keep the math simple.

Also suppose you have three voters who are asked to rank their choices in order of preference. Let’s take a look at the results. In the following table, the candidates are on the top and the voters are on the left.

| Hanselman | Haack | Guthrie | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mariah Carey | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Nicki Minaj | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Keith Urban | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Deadlock! In this particular case, there is no apparent winner. No matter which candidate you pick, two others voters prefer another candidate to that candidate.

Ok, let’s run this like a typical election where you simply get a vote or a non vote (rather than ranking candidates), but we’ll also add more voters. There will be no hanging chads in this election.

| Hanselman | Haack | Guthrie | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mariah Carey | X | ||

| Nicki Minaj | X | ||

| Keith Urban | X | ||

| Randy Jackson | X | ||

| Simon Cowell | X | ||

| Paula Abdul | X | ||

| Jennifer Lopez | X |

In this case, Hanselman is the clear winner with three votes, whereas the other two candidates each have two votes. This is how our elections are held today. But note that Hanselman did not win with the majority (over half) of the votes. He won with a plurality. So can we really say he is the choice of the voters when a majority of people prefer someone else to him?

Both of these situations are examples of Condorcet’s Paradox. Condorcet lived in the late 1700s and was a frilly shirt wearing (but who wasn’t back then?) French mathematician philosopher who advocated crazy ideas like public education and equal rights for women and people of all ages.

He also studied these interesting voting problems and noted that collective preferences are not transitive but can by cyclic.

Transitive and Nontransitive Relations

For those who failed elementary math, or simply forgot it, it might help to define what we mean by transitive. The transitive relation is a relationship between items in a set that has the following property for every item: if the first item is related to a second in this way, and that second item is related to a third in the same way. The first item is also related to the last item.

The classic example is the relation, “is larger than”. If Hanselman’s forehead is larger than Guthrie’s. And Guthrie’s is larger than mine. Then Hanselman’s must be larger than mine. One way to think of it is that this property transitions from the first element to the last.

But not every relationship is transitive. For example, if you are to my right, and you’re friend is to your right. Your friend isn’t necessarily to my right. She could be to my left if we formed an inward triangle.

Condorcet formalized the idea that group preferences are also non-transitive. If people prefer Hanselman to me. And they prefer me to Guthrie. It does not necessarily mean they will prefer Hanselman to Guthrie. It could be that Guthrie would pull a surprise upset when faced head to head with Hanselman.

Historical Examples

In fact, there are historical examples of this occurring in U.S. presidential elections. This is known as the Spoiler Effect. For example, in the 2000 U.S. election, many contend that Ralph Nader siphoned enough votes from Al Gore to deny him a clear victory. Had Nader not been in the race, Al Gore most likely would have won Florida outright. Of course, Nader is only considered a spoiler if enough voters who who voted for him would have voted for Gore had Nader not been in the race to put Gore above Bush in Florida. Multiple polls indicate that this is the case.

In the interest of bipartisanship, Scientific American has another example that negatively affected Republicans in 1976.

Mathematician and political essayist Piergiorgio Odifreddi of the University of Turin in Italy gives an example: In the 1976 U.S. presidential election, Gerald Ford secured the Republican nomination after a close race with Ronald Reagan, and Jimmy Carter beat Ford in the general election, but polls suggested Reagan would have beaten Carter (as indeed he did in 1980).

Reagan had to wait another four years to become President due to that Ford spoiler.

No party is immune from the implications of mathematics.

Condorcet Method

As part of his writings on the voting paradox, Condorcet came up with the Condorcet criterion.

Aside: I have to assume Condorcet had a different name for the criterion when he formulated it and it was named after him by later mathematicians. After all, what kind of vainglorious person applieshis own name to theorems.

A Condorcet winner is a candidate who would win every election if paired one on one against every other candidate. Going back to the prior example, if Hanselman would beat me in a one-on-one election. And he would beat Guthrie in a one-on-one election, then Hanselman would be the Condorcet winner.

It’s important to note that not every election has a Condorcet winner. This is the paradox that Condorcet noted. But if there is a Condorcet winner, one would hope that the method of voting would choose that winner. Not every voting method makes this guarantee. For example, the voting method that declares that the candidate with the most votes wins fails to meet this criterion if there are more than two candidates.

A voting method that always elect the Condorcet winner, if such a winner exists in the election, satisfies the Condorcet criterion and is a Condorcet method. Wouldn’t it be nice if our elections at least satisfied this criteria?

Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem

It might feel comforting to know methods exist that can choose a Condorcet method. But that feeling is fleeting when you add Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem to the mix.

In an attempt to devise a voting system that would be consistent, fair (according to a set of fairness rules he came up with), and always choose a clear winner, Arrow instead proved it was impossible to do so when there are more than two candidates.

In short, the theorem states that no rank-order voting system can be designed that satisfies these three “fairness” criteria:

- If every voter prefers alternative X over alternative Y, then the group prefers X over Y.

- If every voter’s preference between X and Y remains unchanged, then the group’s preference between X and Y will also remain unchanged (even if voters’ preferences between other pairs like X and Z, Y and Z, or Z and W change).

- There is no “dictator”: no single voter possesses the power to always determine the group’s preference.

On one hand, this seems to be an endorsement of the two-party political system we have in the United States. Given only two candidates, the “majority rules” criterion is sufficient to choose the preferred candidate that meets the fairness criteria Arrow proposed.

But of course, politics in real life is so much messier than the nice clean divisions of a math theorem. A voting system can only, at times, choose the most preferred of the options given. But it doesn’t necessarily present us with the best candidates to choose from in the first place.

Comments

23 responses