Structuring Unit Tests

In the past, I’ve tried various schemes to structure my unit tests but never fell into a consistent approach. Pretty much the only rule I had (which I broke all the time) was to write a test class for each class I tested. I would then fill that class with a ton of haphazard test methods.

That was until I saw the approach that Drew Miller took with NuGet.org. The way he structured the unit tests struck me as odd at first, but quickly won me over. Drew tells me he can’t take all the credit for this approach. This approach came from when he worked at CodePlex, and builds upon practices he learned from Brad Wilson and Jim Newkirk. That’s the thing I like about Drew, he won’t take credit for other people’s work. Unlike me, of course.

The structure has a test class per class being tested. That’s not so unusual. But what was unusual to me was that he had a nested class for each method being tested.

I’ll provide a simple code example to illustrate this approach and then highlight some of the benefits. The following has two methods for embellishing names with more interesting titles. What it does isn’t really that important for this discussion.

using System;

public class Titleizer

{

public string Titleize(string name)

{

if (String.IsNullOrEmpty(name))

return "Your name is now Phil the Foolish";

return name + " the awesome hearted";

}

public string Knightify(string name, bool male)

{

if (String.IsNullOrEmpty(name))

return "Your name is now Sir Jester";

return (male ? "Sir" : "Dame") + " " + name;

}

}

Under Drew’s system, I’ll have a corresponding top level class, with two embedded classes, one for each method. In each class, I’ll have a series of tests for that method.

Let’s look at a set of potential tests for this class. I wrote xUnit.NET tests for this, but you could apply the same approach with NUnit, mbUnit, or whatever you use.

using Xunit;

public class TitleizerFacts

{

public class TheTitleizerMethod

{

[Fact]

public void ReturnsDefaultTitleForNullName()

{

// Test code

}

[Fact]

public void AppendsTitleToName()

{

// Test code

}

}

public class TheKnightifyMethod

{

[Fact]

public void ReturnsDefaultTitleForNullName()

{

// Test code

}

[Fact]

public void AppendsSirToMaleNames()

{

// Test code

}

[Fact]

public void AppendsDameToFemaleNames()

{

// Test code

}

}

}

Pretty simple, right? If you want to see a real-world example, look at these tests of the user service within NuGet.org.

So why do this at all? Why not stick with the old way I’ve done in the past?

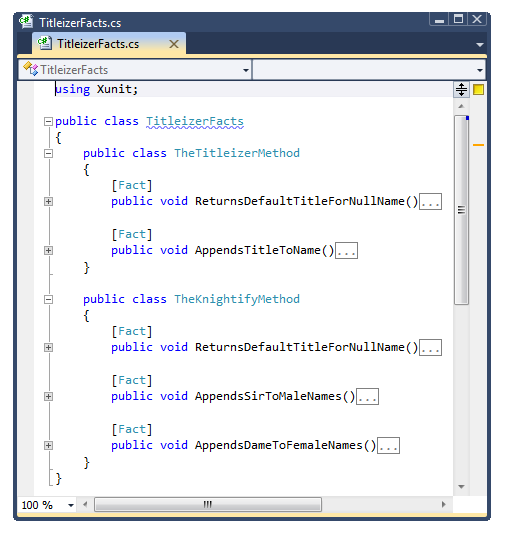

Well for one thing, it’s a nice way to keep tests organized. All the

tests (or facts) for a method are grouped together. For example, if you

use the CTRL+M, CTRL+O shortcut to collapse method bodies, you can

easily scan your tests and read them like a spec for your code.

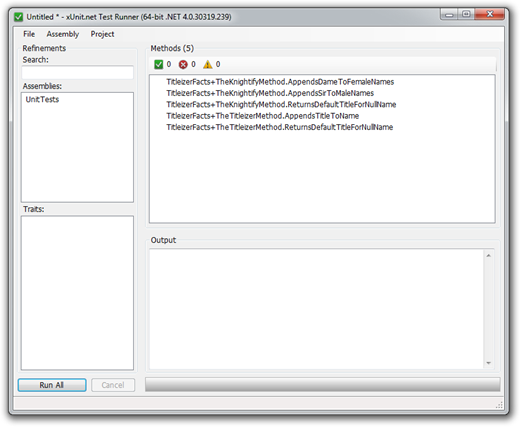

You also get the same effect if you run your tests in a test runner such as the xUnit test runner:

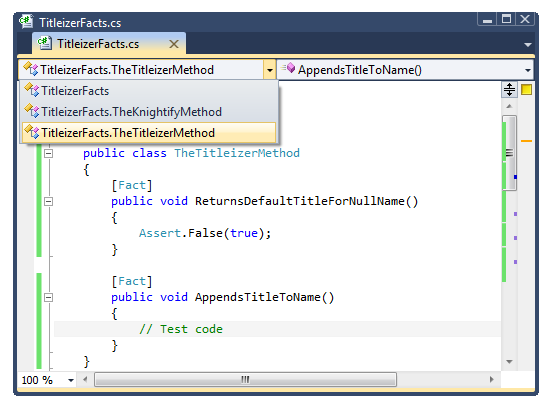

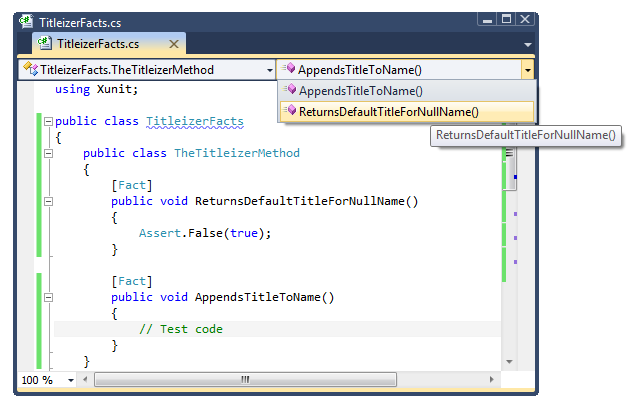

When the test class file is open in Visual Studio, the class drop down provides a quick way to see a list of the methods you have tests for.

This makes it easy to then see all the tests for a given method by using the drop down on the right.

It’s a minor change to my existing practices, but one that I’ve grown to like a lot and hope to apply in all my projects in the future.

Update: Several folks asked about how to have common setup code for all tests. ZenDeveloper has a simple solution in which the nested child classes simply inherit the outer parent class. Thus they’ll all share the same setup code.

Comments

64 responses