Anatomy of a Cross-site Request Forgery Attack

A Cross-site request forgery attack, also known as CSRF or XSRF (pronounced sea-surf) is the less well known, but equally dangerous, cousin of the Cross Site Scripting (XSS) attack. Yeah, they come from a rough family.

CSRF is a form of confused deputy attack. Imagine you’re a malcontent who wants to harm another person in a maximum security jail. You’re probably going to have a tough time reaching that person due to your lack of proper credentials. A potentially easier approach to accomplish your misdeed is to confuse a deputy to misuse his authority to commit the dastardly act on your behalf. That’s a much more effective strategy for causing mayhem!

In the case of a CSRF attack, the confused deputy is your browser. After logging into a typical website, the website will issue your browser an authentication token within a cookie. Each subsequent request to sends the cookie back to the site to let the site know that you are authorized to take whatever action you’re taking.

Suppose you visit a malicious website soon after visiting your bank website. Your session on the previous site might still be valid (though most bank websites guard against this carefully). Thus, visiting a carefully crafted malicious website (perhaps you clicked on a spam link) could cause a form post to the previous website. Your browser would send the authentication cookie back to that site and appear to be making a request on your behalf, even though you did not intend to do so.

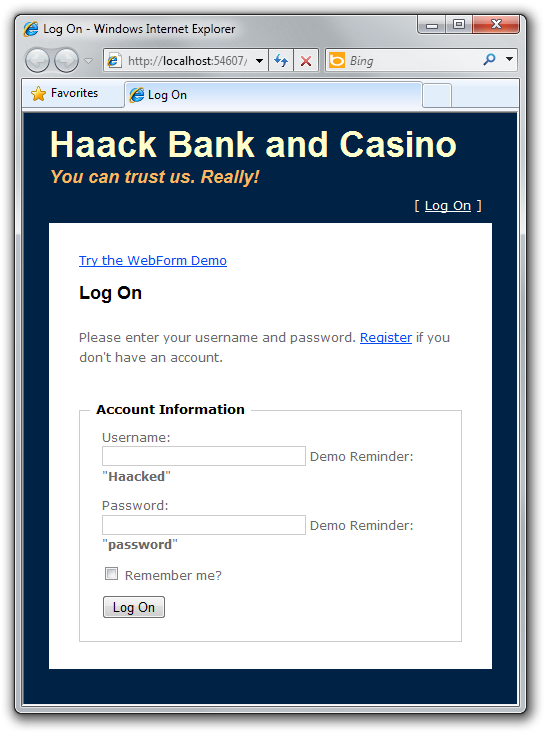

Let’s take a look at a concrete example to make this clear. This example is the same one I demonstrated as part of my ASP.NET MVC Ninjas on Fire Black Belt Tips talk at Mix in Las Vegas. Feel free to download the source for this sample and follow along.

Here’s a simple banking website I wrote. If your banking site looks like this one, I recommend running away.

The

site properly blocks anonymous users from taking any action. You can see

that in the code for the controller:

The

site properly blocks anonymous users from taking any action. You can see

that in the code for the controller:

[Authorize]

public class HomeController : Controller

{

//...

}

Notice that we use the AuthorizeAttribute on the controller (without

specifying any roles) to specify that all actions of this controller

require the user to be authentication.

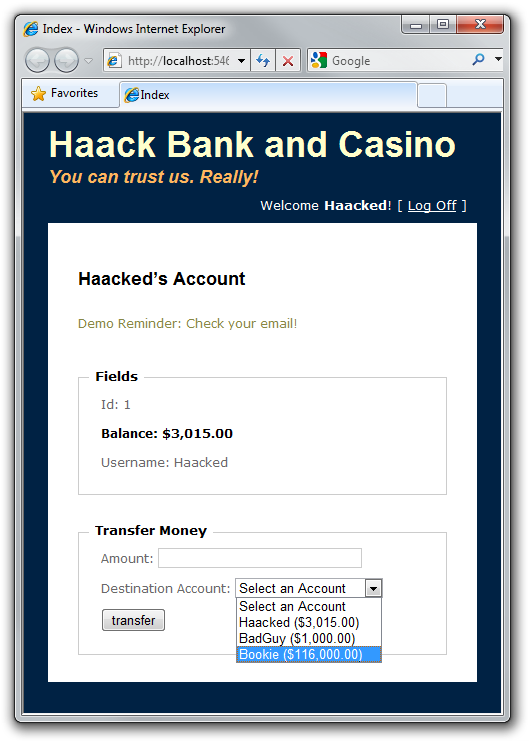

After logging in, we get a simple form that allows us to transfer money to another account in the bank. Note that for the sake of the demo, I’ve included an information disclosure vulnerability by allowing you to see the balance for other bank members. ;)

To transfer money to my Bookie, for example, I can enter an amount of $1000, select the Bookie account, and then click Transfer. The following shows the HTTP POST that is sent to the website (slightly edited for brevity):

POST /Home/Transfer HTTP/1.1 Referer: http://localhost:54607/csrf-mvc.html User-Agent: ... Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded Host: 127.0.0.1:54607 Content-Length: 34 Cookie: .ASPXAUTH=98A250...03BB37 Amount=1000&destinationAccountId=3

There are three important things to notice here. We are posting to a

well known URL, /Home/Transfer, we are sending a cookie, .ASPXAUTH,

which lets the site know we are already logged in, and we are posting

some data (Amount=1000&destinationAccountId=3), namely the amount we

want to transfer and the account id we want to transfer to. Let’s

briefly look at the code that executes the transfer.

[AcceptVerbs(HttpVerbs.Post)]

public ActionResult Transfer(int destinationAccountId, double amount) {

string username = User.Identity.Name;

Account source = _context.Accounts.First(a => a.Username == username);

Account destination = _context.Accounts.FirstOrDefault(

a => a.Id == destinationAccountId);

source.Balance -= amount;

destination.Balance += amount;

_context.SubmitChanges();

return RedirectToAction("Index");

}

Disclaimer: Do not write code like this. This code is for demonstration purposes only. For example, I don’t ensure that amount non-negative, which means you can enter a negative value to transfer money from another account. Like I said, if you see a bank website like this, run!

The code is straightforward. We simply transfer money from one account to another. At this point, everything looks fine. We’re making sure the user is logged in before we transfer money. And we are making sure that this method can only be called from a POST request and not a GET request (this last point is important. Never allow changes to data via a GET request).So what could go wrong?

Well BadGuy, another bank user has an idea. He sets up a website that has a page with the following code:

<html>

<head>

<title></title>

</head>

<body>

<form name="badform" method="post"

action="http://localhost:54607/Home/Transfer">

<input type="hidden" name="destinationAccountId" value="2" />

<input type="hidden" name="amount" value="1000" />

</form>

<script>

document.badform.submit();

</script>

</body>

</html>

What he’s done here is create an HTML page that replicates the fields in

bank transfer form as hidden inputs and then runs some JavaScript to

submit the form. The form has its action set to post to the bank’s

URL.

When you visit this page it makes a form post back to the bank site. If you want to try this out, I am hosting this HTML here. You have to make sure the website sample code is running on your machine before you click that link to see it working.

Let’s look at the contents of that form post.

POST /Home/Transfer HTTP/1.1 Referer: https://haacked.com/demos/csrf-mvc.html User-Agent: ... Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded Host: 127.0.0.1:54607 Content-Length: 34 Cookie: .ASPXAUTH=98A250...03BB37 Amount=1000&destinationAccountId=2

It looks exactly the same as the one before, except the Referer is

different. When the unsuspecting bank user visited the bad guy’s

website, it recreated a form post to transfer funds, and the browser

unwittingly sent the still active session cookie containing the user’s

authentication information.

The end result is that I’m out of $1000 and BadGuy has his bank account increased by $1000. Drat!

It might seem that you could rely on the checking the Referer to

prevent this attack, but some proxy servers etc… will strip out the

Referer field in order to maintain privacy. Also, there may be ways to

spoof the Referer field. Another mitigation is to constantly change

the URL used for performing sensitive operations like this.

In general, the standard approach to mitigating CSRF attacks is to render a “canary” in the form (typically a hidden input) that the attacker couldn’t know or compute. When the form is submitted, the server validates that the submitted canary is correct. Now this assumes that the browser is trusted since the point of the attack is to get the general public to misuse their own browser’s authority.

It turns out this is mostly a reasonable assumption since browsers do

not allow using XmlHttp to make a cross-domain GET request. This makes

it difficult for the attacker to obtain the canary using the current

user’s credentials. However, a bug in an older browser, or in a browser

plugin, might allow alternate means for the bad guy’s site to grab the

current user’s canary.

The mitigation in ASP.NET MVC is to use the AntiForgery helpers. Steve Sanderson has a great post detailing their usage.

The first step is to add the ValidateAntiForgeryTokenAttribute to the

action method. This will validate the “canary”.

[ValidateAntiForgeryToken]

public ActionResult Transfer(int destinationAccountId, double amount) {

///... code you've already seen ...

}

The next step is to add the canary to the form in your view via the

Html.AntiForgeryToken() method.

The following shows the relevant section of the view.

<% using (Html.BeginForm("Transfer", "Home")) { %>

<p>

<label for="Amount">Amount:</legend>

<%= Html.TextBox("Amount")%>

</p>

<p>

<label for="destinationAccountId">

Destination Account:

</legend>

<%= Html.DropDownList("destinationAccountId", "Select an Account") %>

</p>

<p>

<%= Html.AntiForgeryToken() %>

<input type="submit" value="transfer" />

</p>

<% } %>

When you view source, you’ll see the following hidden input.

<input name="__RequestVerificationToken"

type="hidden"

value="WaE634+3jjeuJFgcVB7FMKNzOxKrPq/WwQmU7iqD7PxyTtf8H8M3hre+VUZY1Hxf" />

At the same time, we also issue a cookie with that value encrypted. When the form post is submitted, we compare the cookie value to the submitted verification token and ensure that they match.

Should you be worried?

The point of this post is not to be alarmist, but to raise awareness. Most sites will never really have to worry about this attack in the first place. If your site is not well known or doesn’t manage valuable resources that can be transferred to others, then it’s not as likely to be targeted by a mass phishing attack by those looking to make a buck.

Of course, financial gain is not the only motivation for a CSRF attack. Some people are just a-holes and like to grief large popular sites. For example, a bad guy might use this attack to try and post stories on a popular link aggregator site like Digg.

One point I would like to stress is that it is very important to never allow any changes to data via GET requests. To understand why, check out this post as well as this story about the Google Web Accelerator.

What about Web Forms?

It turns out Web Forms are not immune to this attack by default. I have a follow-up post that talks about this and the mitigation.

If you missed the link to the sample code before, you can download the source here (compiled against ASP.NET MVC 2).

Comments

30 responses